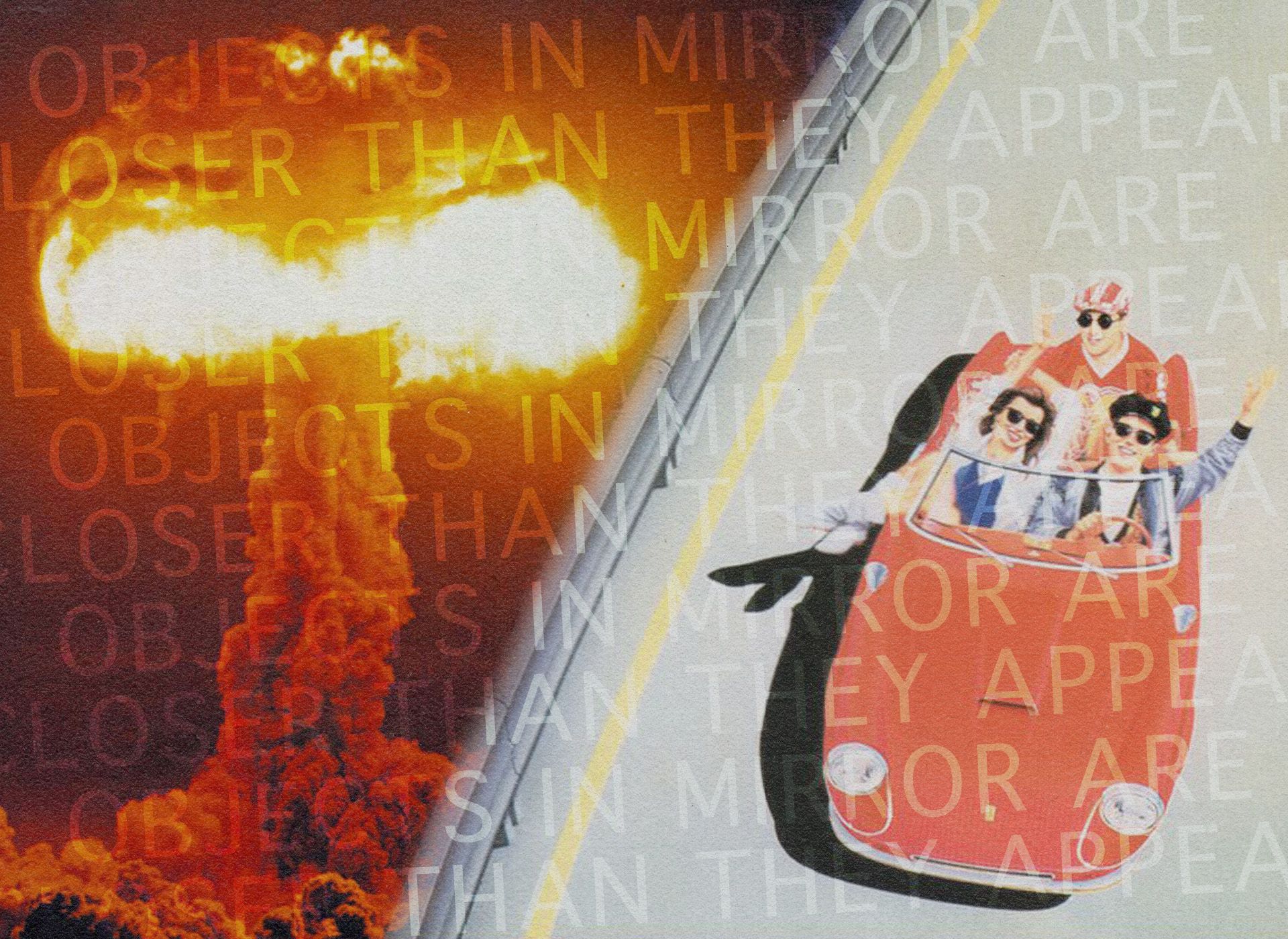

The War On Cars

Despite activists' best efforts, cars are not going anywhere anytime soon

I like my truck

I like my girlfriend

I like to take her out to dinner

I like a movie now and then

...but I love this car.

Toby Keith, 'I Love This Bar' (Redux)

In Nashville, you need a car. It’s inconvenient and egregiously time-consuming to navigate the city in any other manner. Tennessee, in fact, is among the most car-centric states in the country. According to a study from CompareCarInsurance.com, Memphis is the most car-dependent metro area in the country, with Nashville close behind it at number two.

Another study ranks Nashville second in cities with the highest rate of car ownership. According to this study, 96 percent of households in Nashville have access to a vehicle—and for good reason.

Nashville is among the least densely populated cities in the country, with an average density of 1,505 people per square mile. Compare that to, say, Seattle, Washington—among the least car-dependent cities in the country—and its 9,248 people per square mile, and it's easy to understand why cars are so necessary for Nashville residents.

Even despite these very firm realities, there continues to be a loud contingent here clamoring for bus line expansions, umpteen bike lanes, new sidewalks, and all manner of bright fluorescent road markers in an attempt to inch the city toward some kind of walkable utopia.

To study this contingent’s work, try pulling onto Belmont Boulevard from any of its numerous side streets without pausing momentarily to assess the carnage of signs, markers, and lines as you divine your next move. I throw up a prayer every time I pull out into this miasma of confusion, hoping I don’t plow over a biker or t-bone a Belmont student.

What’s surprising about this whole debate is how reminiscent the progressive position—abolishing the personal automobile in favor of mass public transit—is to the conservative approach to such issues. The reasons they give are multitudinous, but lately, they’ve mostly hinged on the environmental benefits of packing people like sardines onto buses and trains.

In A Pattern Language, among the most famous books on urban planning, Christopher Alexander ranks the problems caused by the automobile thusly: air pollution, noise, danger, ill health, congestion, parking problem, eyesore.

Back before the automobile, these transit activists like to tell us, people lived close together in these things called communities. But most importantly, their carbon footprints were smaller—almost non-existent—and if you wanted to talk to grandma, well, you just walked over to her house and knocked on her door, no gas needed.

If you’ve spent any amount of time in a truly walkable city, you know the pleasures it can bring. I’ve had the fortune to spend a fair amount of time in such places: Melbourne, Vienna, San Francisco stick out. But what these places express with their accessibility always felt debilitating in some way; confining might be a better word for it.

Originally intending to undo “the mistakes which have happened in the growth of metropolitan areas of the east,” Los Angeles has since become a suburban nightmare, but in the 1930s, it was affordable, 93 percent of the city’s residents lived in single-family homes, and residents were four times more likely to own a car than Chicagoans.

Los Angeles is now beset by its obvious faults, but the original goal of the city was to look beyond the crowded urban areas that, prior to the vehicle, were the only option. The City of Angels appealed to those people who sought new lifestyles in a Mediterranean climate. This was a better city for you, not for the masses—or for the environment, as it’d be represented today.

Around this time, Frank Lloyd Wright began to develop his ideas for a city template he called the Broadacre, which would account for the advent of the automobile and the expressed interest of citizens in living in single-family bungalows. Addressing Princeton University in 1930, Wright declared, “I believe the city, as we know it today, is to die. . . ”

His Broadacre was an attempt at empirically reckoning with the developments of the time. In contradistinction to Le Corbusier’s more rational, utopian, high-density approach, Wright worked to give form to what already existed. Sensing the upward trend in mobility and decentralization that the automobile would inspire, he declared that an “acre to the family should be the democratic minimum.”

Wright’s suburban vision was not without its flaws, but he understood something fundamental, something most of his contemporaries who lamented the advent of the vehicle missed: “The highway is becoming the horizontal line of Freedom extending from ocean to ocean tying woods, streams, mountains, and plains together.” The man seated in his automobile provided a “new standard of space measurement.”

He fully understood the beauty of the automobile and what it offered man on a human level. Vehicles expand our freedom of movement, they widen the scope of accessible places and spaces, and, if treated as such, can become tools tied as tightly to us as a trusty hammer or—to use a more modern metaphor—our smartphones. At the root of the American genesis, you’ll find the same virtues expressed throughout: an emphasis on self-reliance, responsibility, and the love of open space. Cars—not to mention how fun they are to drive—play into all of these.

The ask that you give up your car is the ask that you invert your moral compass, give up your selfish, pleasure-seeking ways, and surrender it all on the altar of the “greater good” to people who know better. This is definitively an un-American impulse.

A more mature approach to Nashville’s growth issues as they pertain to transportation would be to start with the permanence of cars and people’s preference for houses over apartments, then work outward from there. What would a visionary approach to Nashville’s growth and congestion issues look like?

It would start with de-emphasizing public transportation and working with surrounding counties to ease the strain of our very car-centric area, say by developing new city centers away from Broadway. Instead, our city leaders nickel and dime for signage, throw fits over a bridge design, and harangue over their not being able to smoke a joint in public or get an abortion… all while the real movers and shakers turn Nashville into a drunken playground for developers and tourists.

Nashville has the opportunity to express a new vision of urbanism. In fact, the very real constraints on it demand such a vision. Eliminating cars is not a realistic vision, nor should it be taken seriously on a local or national level. Americans like their cars and their houses. Frank Lloyd Wright is not the only one who reckoned with these problems, and it’d be refreshing to see a city leader project some vision of Nashville’s future not contingent on tourism and a 20th-century understanding of public transportation.