The Root Of It All

One Man's Quest for Ginseng in East Tennessee

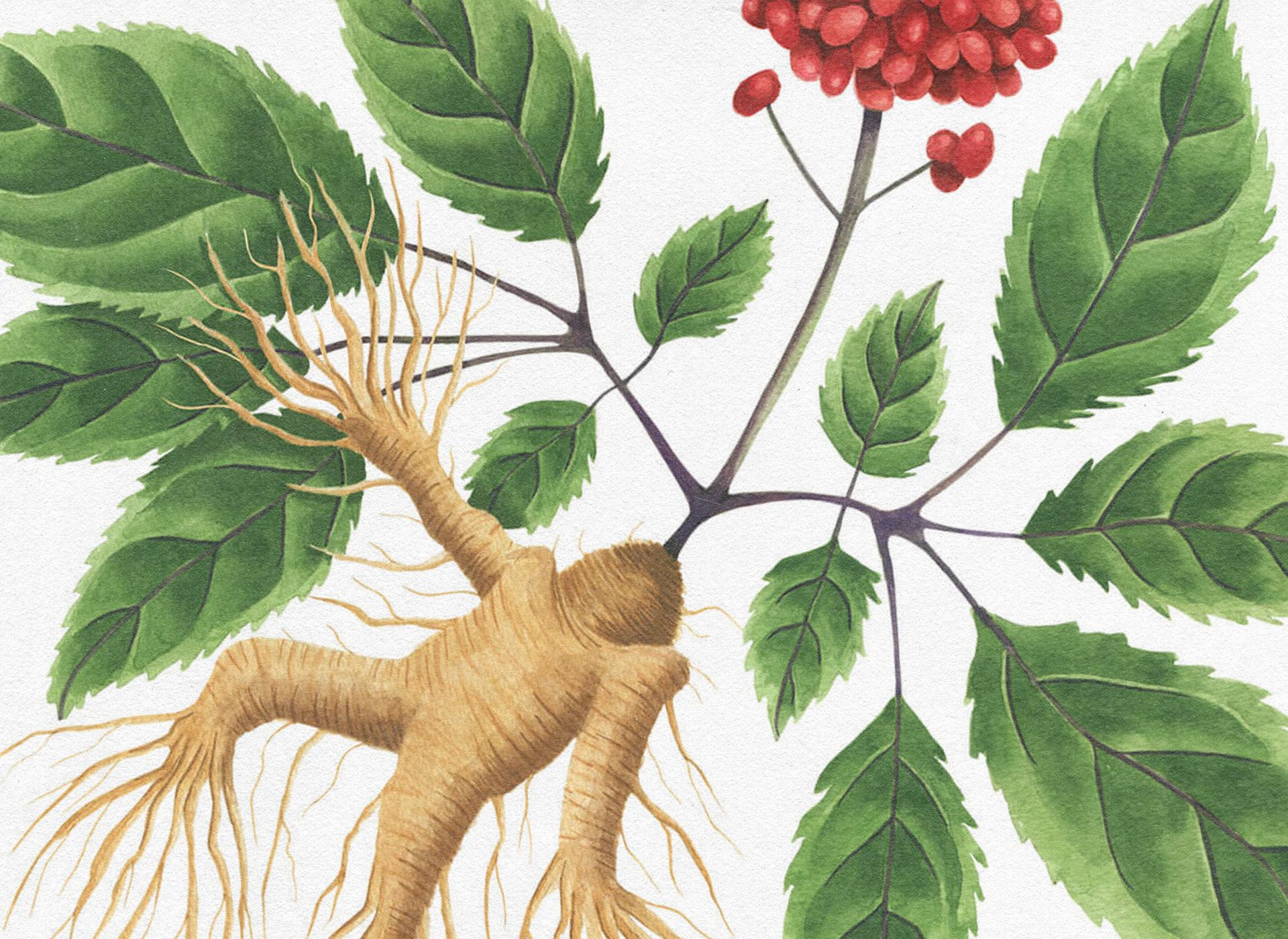

Ginseng is an herb most treasured for its root, which has been used for millenia for the health benefits it bestows. Referred to sometimes as “man-root” due to its shape resembling a little person, the majority of its mass sits underground, showing itself above ground with pointed, serrated leaves in bunches of five. In the spring, small light green berries appear, which turn red and fall to the ground in the fall. Found in mountain ranges across the planet (mostly in Asia and North America), ginseng both benefits and suffers from extreme popularity.

In the misty ranges of Eastern Tennessee, American Ginseng is worth $550 a pound when dried, leading to plenty of “poachers” who will clear it all away for a quick buck—a misdemeanor that can put them in prison for up to six months. Local hunters, however, know the importance of saving seeds, replanting, and cultivating more for later. In Cleveland, Tennessee, at the head office of the Cherokee National Forest, one can put in a bid for a permit to pick ginseng—along with the promise that they will stay within the allotted area and replant consistently. “If you get busted somewhere you’re not supposed to be, you get in a lot of trouble,” says “Sunheart”, a local who finds and cultivates ginseng on his own land regularly. He says replanting found seeds is Ginseng 101.

Sunheart is an East Tennessee native who’s put much of his time and energy into properly stewarding the land, “living by the seasons,” and homesteading. A singular character—too metal to be a hippie, too hippie to be metal, and too country to be either one—he lives in a small cabin in the mountains, where he grows an eclectic garden of fruits, vegetables, and herbs, both culinary and medicinal, across one large plot. When Sunheart isn’t tending to his garden, building, cooking, or enjoying the thick forest with his dog, Strawberry, he’ll be found absolutely shredding guitar in the tiny cabin he has cleaned up and restructured.

Ginseng has captured his attention in part because of its relative abundance where he lives but also finds its roots in a familial interest in traditional medicine. His mother and sister both work as massage therapists, and his sister is in the process of opening an ayurvedic medicine shop, which he hopes to contribute to. Spending a day with Sunheart will expose you to a number of gorgeous forest locales, in a seance with the Native American folklore that surrounds them.

WHY IS IT SO SPECIAL?

Sunheart doesn’t sell his ginseng. He only collects seeds for replanting and roots for making his own tea. “Most do it for money,” he explains. “But some are still old school and do it for the health benefits.” Ginseng has been used for thousands of years as an all around health tonic. An anti-inflammatory rich in beneficial antioxidants, it has been proven to improve brain function and memory, boost the immune system, lower blood sugar, and reduce fatigue. There are shops in China entirely devoted to the sale of ginseng, both fresh and dried. Walls are lined with variations of the root from floor to ceiling and sold for a pretty penny.

Sunheart likes to brew his ginseng into a tea with rosemary he grows. “I didn’t notice anything right away,” he laughs, “I’m sure it’s one of those things you gotta drink for like a week straight.” As with most herbal medicine, benefits and changes will be subtle and occur over time.

The use of ginseng for its health benefits has its foundation in the ancient medicinal traditions of both India and China. One of the first known records of ginseng is found in a book from 196 A.D. called the Shen Nong Pharmacopoeia, which defined it as a “noble herb” of the highest tier. This is because ginseng poses no threat to humans (even with overconsumption) and bestows plenty of medicinal benefits. As the Shen Nong Pharmacopoeia is believed to be a compendium of long held Chinese oral medicinal traditions, it’s certain that ginseng has been used for over two thousand years. In the 16th century, its popularity was so immense that in Korea and China, wars were fought to control the land where it grew.

THE TASK OF CULTIVATION

When his sister fully opens her shop, Sunheart hopes to supply her with the valuable root—but only after he has spent a few years planting more of it. “It could be a cash crop as it gets older,” he says, but he can’t commit to such an endeavor realistically or ethically right now. Because of its popularity with poachers, it is extremely important to plant more wild ginseng. “People would use my property and pick it clean,” tells Sunheart of his property before he arrived there. Poachers left only very young ginseng in their wake, focusing on collecting all of the older and larger roots. He can tell the age, he explains, by the “nodes”: the stems that leave the ground from the root. Over the years, he has only found plants with three nodes—a sure sign that it is only in its first year of life. “My main goal is to grow it older.” Aged plants will display five or more nodes, and so far he hasn’t found even one in the area.

While ginseng will show above ground with light green berries in the springtime, the best time to go looking is in September and October when the berries are red. Not only is it easier to spot with bright red berries, but this is the time when its seeds are ready to be replanted. “My phone tells me the days I took pics,” laughs Sunheart. “That’s how I tell when the best season is.” After October, the plants become docile with the cold and they are much more difficult to find. At this point, the ginseng is still there, but nearly impossible to spot as it withdraws underground for the winter.

With only a short harvesting season, finding ginseng plants requires a lot of patience, and replanting them requires selflessness. Sunheart must commit all of the labor and time of the poachers without the immediate cash benefit. The process starts with looking around certain areas—namely, shady coves with good water flow. After searching for a while, he can generally find ginseng in places where water flows and angel ferns grow. Hunting for ginseng is time consuming, but altogether he finds it to be a pleasant activity: “It’s real long, slow, and it gives you time to just chill and look at everything.” When he finally does spot some of the plants, with their red berries and five-pointed, serrated leaves low to the ground, he knows his senses have sharpened to the search. “Once you see ‘em you can’t unsee ‘em. I call it ‘sing because it sings to me,” he chuckles. When he starts to get a feel for the plants in a given area, he’ll say to himself, “It’s singin’ now, telling you where to go.” This year alone, he has replanted seventy seeds on the mountain and forest around his property. After two or three more years, he hopes that the mountain will have plenty of healthy, five-node plants.

A LEARNING EXPERIENCE

Many of the plants he finds he uses in his own small scale experiments to understand the plant, how it works, and where it grows. For example, when Sunheart found that no plants were growing on the sunny side of his mountain, he tried to plant some seeds there. He had been wondering if it was possible that all of the ginseng on one side had been picked more than the rest, but quickly discovered this wasn’t the case: his plants in the sunnier part of the forest simply refused to grow.

Ginseng is used both fresh and dried, so he also has done his own drying by sunlight. While fresh ginseng root has the density of any edible root (like a slightly harder carrot) he found it surprising how “hard and woody” it became after drying. When chopping it up for use in tea, a lot of time was spent hacking and chopping away to free the small chips of ginseng from the fully dried root.

Ultimately, he embraces all parts of the process. While others may scour the forest, ripping up every bit of valuable root they can find with no concern for anything beyond the few hundred dollars they’ll soon pad their pockets with, he cares for the forest and each plant that lives in it. He accepts what he finds as a gift and helps the land produce more by replanting. Some may expect their land to work for them, but the oldest traditions teach us to work alongside the land.