The Pleasures of Mob Rule

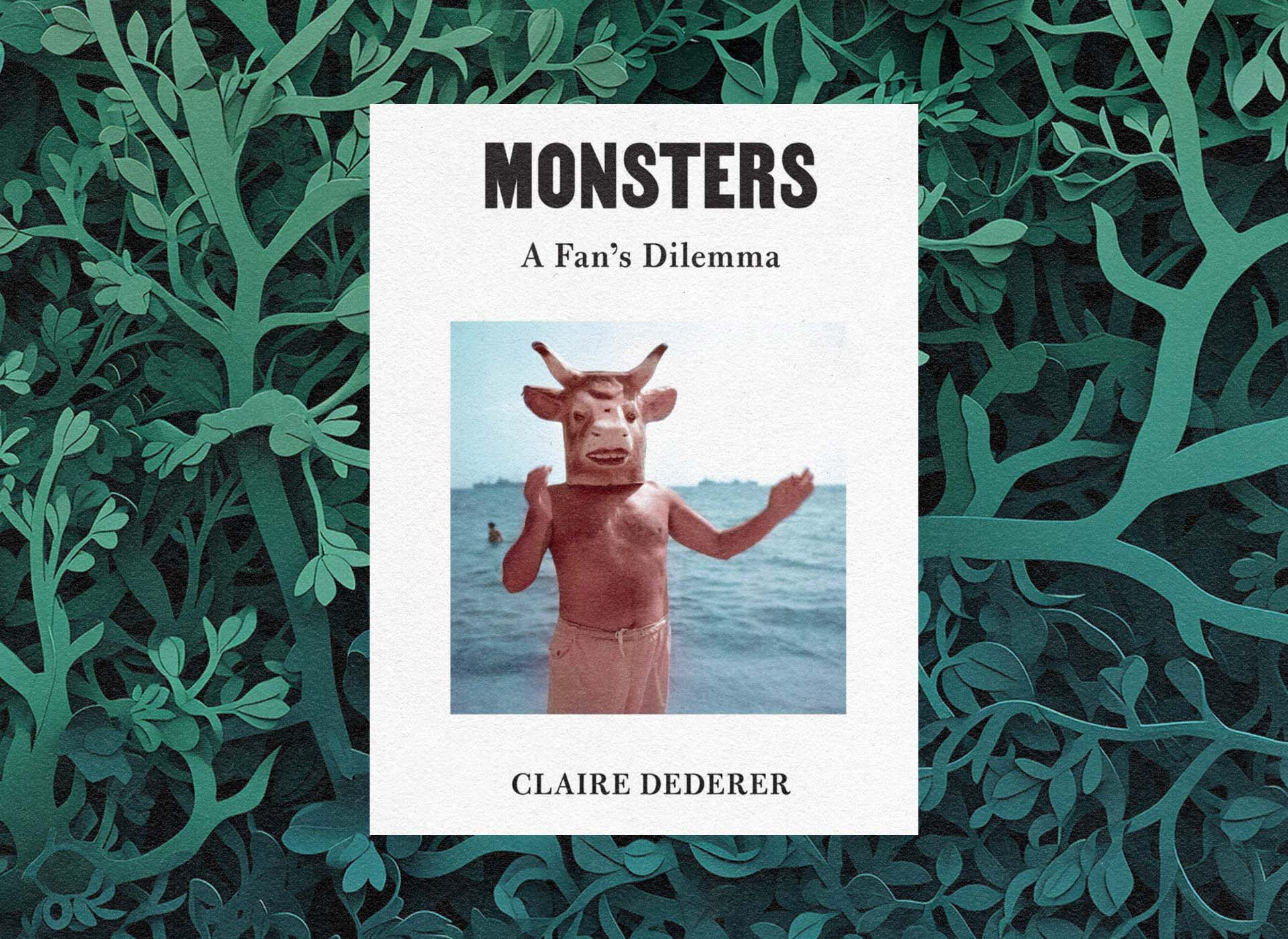

A review of Claire Dederer’s "Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma"

Claire Dederer adores Chinatown and Annie Hall. This affinity for the films of Roman Polanksi and Woody Allen poses a major problem for a memoirist who lives on a houseboat in the Pacific Northwest and makes her living as a creative writing professor and regular contributor to The New York Times. But Dederer is also the rarest of literary authors in our current moment: a self-reflective thinker with a devotion to grappling with thorny problems in ways that won’t drive the monetization of her online presence.

While it may appear that the last thing the world needs is another perspective on #MeToo from someone firmly entrenched in legacy media, Monsters both proves itself an indispensable read and a full-throated defense of the book form as a counter to the online outrage that indiscriminately destroys lives in the name of self-righteous zeal.

“What do we do with the art of monstrous men?” Dederer first asked in a November 2017 essay for The Paris Review. During the throes of #MeToo, she managed to retain an artist’s skepticism of the always online sans-culottes waiting to topple the next powerful dude. Now armed with full knowledge of America circa 2022, she revists the period with an even more keen sense critical lens. “The feminism I knew was a feminism that found fault. That pointed–j'accuse. As I understood it, there were two ways of being: you could be a feminist who called men monsters, or you could ignore the problem,” she writes. “I considered myself a feminist, but at the same time I had an uneasy feeling that the pointing of fingers was not the whole story. A feminism that denounced, that punished was starting to feel like a trap.”

For Dederer, the intervening years between essay and book has led her to think about sullied reputations as “the stain,” a glaring flaw in a gorgeous tapestry. Some may see it as spoiling the work. Others may overlook it. But, it’s now an irrevocable part of artistic legacy. Beginning with her ruminations on Polanski and Allen, Dederere expands her list of perpetrators past and present to include Wagner, Hemingway, Picasso, Miles Davis, and Michael Jackson. Her defense of Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita is an absorbing and timeless piece of popular literary criticism that is essential for anyone reading the controversial classic, especially those doing so in an academic climate often vocally at odds with Dederer’s contention that “We shouldn’t punish artists for their subject matter.”

Crucially, Dederer also brings monstrous women into the fold by fleshing out her initial thesis with long-ranging chapters on child abandoners Doris Lessing, Joni Mitchell, and Sylvia Plath–whose suicide by gas oven has long served as a symbol of the dual demands of artistry and motherhood. Dederer is a critical enough writer to acknowledge the sexual difference between male and female monsters: the larger-than-life genius who takes advantage of the women in their lives and the women who sacrificed motherhood to take up the mantle of genius while dealing with the fallout. It’s a cogent and convincing take that could serve as the impetus for a fruitful conversation of gender dynamics.

Dederer may include an obligatory chapter on J.K. Rowling’s second life as trans skeptic. However, her seemingly ubiquitous definition of “monster” doesn’t fall into the mire of accusations unwittingly highlighting the kangaroo court that ultimately became #MeToo’s undoing. It serves to bring us all into the fold. “We live in a biographical moment, and if you look hard enough at anyone, you can probably find at least a little stain,” she writes. “Everyone who has a biography–that is, everyone alive–is either canceled or about to be canceled.”

Such a line shouldn’t be this much of a revelation. But one must remember that the onset of the Trump years spawned a precipitous slide even before #MeToo in which celebrities as innocuous as The Office’s Jenna Fischer advocated for the destruction of every copy of Bernardo Bertolucci’s Last Tango in Paris because the media dredged up long-ago-published accusations from star Maria Schnieder as some sort of weird cope for the election of the orange man. Of course, a director half a century removed from the sexual revolution would avoid such behavior today, but that such extreme censorship ever became acceptable in public discourse gives Dederer’s work a sense of urgency that she handles with aplomb: “What do we do with the art of monsters from the past? Look for ourselves there–in the monstrousness. Look for mirrors of what we are, rather than evidence for how wonderful we’ve become.”

Amid such unflappability, Dederer manages to call attention to her own complicity without falling victim to the worst tendencies of memoir navel-gazing. As the book reaches its final chapters, the author recounts her revelation that she had an alcohol problem, an admission that did much to solidify her years-long hand-wringing over those monstrous men. “Monsters are just people,” she writes. “I don’t think I would have been able to accept the humanity of monsters if I hadn’t been a drunk and if I hadn’t quit. If I hadn’t been forced, in this way, to acknowledge my own monstrosity.”

Unfortunately, writers are just people too and, in order not to be whisked away into whatever the public intellectual iteration of Siberia is, a book this nuanced must still signal its allegiance to the party line. Despite clearly developing a dimensional view of monstrous gender politics, Dederer’s inescapable commentary on Trump and Justice Kavanaugh’s misconduct allegations never rise above the treatment one would expect them to receive from reading her dust jacket bio.

In the face of Ernest Hemingway’s well-documented history of domestic abuse, Dederer has the foresight to ask “What did it cost Hemingway to be so much one thing (a man) and never its opposite?” But, she exempts much more flimsy accusations against her political opponents from her approach. Never mind that her comments on monstrous male genius and Trump’s “Grab ‘em by the pussy” remarks reach the same point about power and the cult of personality from entirely different ends. Some monsters just need slaying.

Regardless, while mainstream outlets and online radicals double down on their claims cancel culture is a myth, Dederer is an honest enough writer to proclaim, “The way you consume art doesn’t make you a bad person or a good one. You’ll have to find some other way to accomplish that.” For many of her readers, such a statement may not sit pretty. Yet, as Dederere reminds us, there is a third option between outright erasure and just shrugging it all off as Chinatown.